The Backstory of M^0

A New Way to Issue Cryptodollars Onchain

M^0 is a decentralized cryptodollar issuance network. But what does this mean? Is it yet another stablecoin project? How does M, its stablecoin, differ from others like USDC or DAI?

There are two primary ways to explore new projects. One approach is to dive into the whitepaper and technical analyses that dissect the project’s mechanics. And plenty of excellent resources already exist for M^0.

The other approach is to understand the story behind its creation: the motivations, the vision, and the problems it seeks to address. That’s the purpose of this piece. I wanted to start with the fundamental of money itself and build a foundation for why M^0 was conceived.

Although we use it everyday, money is a surprisingly complex concept. To breakdown into easier pieces, I’ll first introduce four aspects of money that can be connected like Lego blocks: (i) Money Creation, (ii) Singleness of Money, (iii) the Monetary Triangle, and (iv) the Monetary Stack.

In preparing this piece, I drew insights from M^0’s co-founder Luca Prosperi’s Substack, articles on M^0 Research, and various studies on the monetary system. I’ve done my best to ensure the information is accurate, but please feel free to point out any inaccuracies.

I. Money Creation

Let’s start with the very basic. How is money created?

In a fiat monetary system, money is primarily created when commercial banks (which we’ll simply refer to as “banks”) extend loans to their customers. This doesn’t mean the banks can create money out of thin air at will. Before money can be created, the bank must first receive something of value: your promise to repay the loan.

Assume you need financing to buy a car. You’ll go to your local bank and apply for a loan. Once your application is approved, the bank credits your account with a deposit equivalent to the loan amount. New money is created in this moment.

When you transfer the funds to the car seller, the deposit may move to a different bank if the seller uses another institution. However, the money remains within the banking system until you start repaying the loan. Money is created through lending and destroyed through repayment.

Figure 1: Money creation through making additional loans

Source: Money Creation in the Modern Economy (Bank of England)

This mechanism is not an “infinite money glitch” because there are constraints on how much money a bank can create. These limits are set by monetary policy, which is controlled by central banks. We’ll cover the genesis of central banks in the next section, but for now, think of them as the “bank’s bank”.

Central banks ultimately control the demand for new loans by setting short-term interest rates, specifically the interest paid on reserves that banks hold at the central bank. These rates influence how willing the banks are to lend in the money market, where central banks and other financial institutions lend to each other.

As these interbank rates change, they ripple through the economy and affect the interest rates that banks charge borrowers. Interest rates play a critical role in money supply because they determine the profitability of lending for banks, who earn money from the spread between the rates at which they lend and their cost of funds.

By setting the “price of money”, central banks indirectly influence the overall money supply. A looser monetary policy, which lowers borrowing rates, encourages more lending and expands the money supply, while a tighter policy has the opposite effect.

II. Singleness of Money

Why were central banks created?

Before the establishment of central banks, individual banks issued their own bank notes (essentially, their own forms of money) to lend to customers. If a bank failed, however, its notes became worthless.

As a result, the value of each bank’s notes fluctuated depending on the institution’s perceived stability. For instance, notes from prominent New York banks were considered safer and, therefore, traded closer to the face value of a dollar. In contrast, notes from less reputable banks often traded at a discount relative to their stated value.

A bank’s note typically only circulated at full value within the local area where the bank operated. The further the distance from the region, the larger the discount tended to be. This fragmentation created significant inefficiencies and made trade across regions cumbersome.

Central banks emerged to solve this problem by standardizing the value of money and creating a unified framework for banking stability. Under this system, all member banks are required to maintain reserve accounts at the central bank. If a bank faces a sudden surge in withdrawal requests, it can tap into these reserves to meet the cash demands of its customers.

In return, the central bank ensures that notes issued by any member bank are accepted at face value throughout the system. Additionally, the central bank serves as the lender of last resort. Through its discount window facility, banks can pledge eligible assets as collateral to secure short-term loans, providing them with immediate liquidity in times of need.

Figure 2: An illustration of a system with singleness of money

Source: #54 | M^Zero, Singleness of Money, and Proofs By Contradiction (Dirt Roads)

This structure achieved “singleness of money,” where all bank notes and deposits were treated as equivalent. No longer did people need to worry about the creditworthiness of individual banks or the value of each bank’s note. They simply became money.

To illustrate this concept, I’m going to paraphrase the modern example that Luca used. Suppose I hold an account with J.P. Morgan (JPM). Although the U.S. Dollar (USD) is the official currency of the U.S., the balance in my JPM account technically represents a form of bank money, which we’ll call jpmUSD.

The jpmUSD is pegged to the USD at a 1:1 ratio through JPM’s agreement with the central bank, the Federal Reserve (Fed). I can convert jpmUSD into physical cash or use it interchangeably with other banks’ notes, such as boaUSD or wellsfargoUSD, at a 1:1 rate within the Fed system. In the rare event that JPM struggles to honor this peg, the government’s FDIC insurance would step in and allow me to convert my jpmUSD to actual USD up to $250,000.

This system works so seamlessly that most people overlook the distinction between bank notes (like jpmUSD) and actual central bank money (USD) altogether. It all feels like the same money, which is the essence of achieving singleness of money.

III. The Monetary Triangle

The fiat monetary system requires a continuous flow of new money to sustain economic activity. And the government and central bank rely heavily on banks to distribute this new money through the economy.

Luca describes this system as the “Monetary Triangle”:

Figure 3: Illustration of the monetary triangle

Source: #53 | Banking is Broken, Hallelujah (Dirt Roads)

“The triangle was adopted at Bretton Woods in 1971. Powerful at the centre was Government, designing systems and allocating spending. On the strong side, Central Bank, mandated to control monetary policy and later regulation. On the weak side, Commercial Bank, dealing with clients and managing the infrastructure. It was a fruitful, mutually dependent, relationship.”

- #3 | The Dangerous Ambition Behind CBDCs (Dirt Roads)

Within the triangle, the government's role is to manage public spending and taxation. When it runs a budget deficit, it issues new bonds to finance the shortfall. Central banks and banks often act as a dependable buyers of this state-issued debt, providing the liquidity needed to support government expenditures.

Historically, central banks have lacked the tools to directly allocate money to the public or engage with individual depositors. While Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) could bridge this gap, that discussion is beyond the scope off this post. Instead, central banks focus on regulating the banking system, maintaining monetary stability, and ensuring compliance among financial institutions.

Therefore, the responsibility for funding the economy and expanding the money supply falls on banks. Currently, 97% of all money in circulation is created by banks through loans and deposits, while only a small fraction is issued directly by central banks in the form of physical currency and central bank reserves.

In exchange for providing these services, the banks are permitted to earn a spread between their cost of funds and lending rates. To optimize profitability, they rely on various sources of debt, such as low-cost customer deposits, interbank loans, and more expensive options like subordinated debt. For a deeper dive into how different types of funding impact a bank’s profitability, you can refer to this insightful post.

Because banks play such a critical role in the monetary system, the government and central bank impose strict regulation on their leverage through capital adequacy and leverage ratio requirements. Despite these safeguards, however, banks frequently operate with high leverage, making them vulnerable to financial shocks.

When a bank’s equity is insufficient to absorb losses, it can become insolvent and trigger systemic risks that can destabilize the broader economy. Unfortunately, these crisis are more common than we’d like, as demonstrated by the recent collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB).

Several factors led to the downfall of SVB, but it began with interest rate risk. Like many banks, SVB had invested a significant portion of its assets in long-term U.S. Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities. While these are typically considered safe investments, their value is highly sensitive to changes in interest rates due to their long maturities.

When the Fed began raising interest rates aggressively to combat inflation, the value of SVB’s bond portfolio dropped sharply because bond prices move inversely to interest rates. Although the losses were not immediately realized as the bonds were still held on the balance sheet, they significantly weakened SVB’s financial standing. Unlike other financial institutions, SVB used minimal interest rate hedging, which magnified its exposure.

Next came liquidity risk. SVB primarily catered to tech startups and VC-backed firms that had amassed substantial deposits during the low interest rate environment. As the tech sector began to struggle and VC funding dried up in 2022, SVB’s depositors started drawing down their balances to fund ongoing operations.

To meet these withdrawal requests, SVB needed liquidity, but a large portion of its capital was locked in long-term bonds that had already lost value. In March 2023, SVB announced it had sold a large portion of its bond portfolio at a loss of approximately $1.8 billion and would raise additional capital to shore up its balance sheet.

This announcement sparked panic among depositors and they rushed to withdraw their money. The sudden surge in withdrawals exceeded SVB’s ability to meet them, forcing the FDIC to step in and take control of the bank on March 10. To prevent further panic and contagion across the financial sector, the government took the extraordinary step of guaranteeing all deposits at SVB, even those above the $250,000 FDIC insurance limit.

While this intervention restored confidence and prevented similar bank runs at other institutions, the SVB collapse, yet again, underscored a crucial vulnerability in the financial system. Banks, despite their central role in money creation and distribution, remain the most fragile component of the monetary triangle.

IV. The Monetary Stack

Just as different technologies can be stacked together to build a digital ecosystem, various forms of money can be layered to create a monetary system.

Let’s revisit the earlier example of USD and jpmUSD. Bank notes like jpmUSD emerged because USD alone couldn’t meet the demands for continuous money creation, and physical cash was inconvenient for everyday transactions.

While both jpmUSD and USD serve as forms of money, jpmUSD (a bankcoin) can be seen as an overlay on top of USD (a coin). In other words, bankcoin is built on the trust and stability of coin, supported through formal agreements with the Fed and the U.S. government.

With the rise of digital finance, however, the public began seeking additional features that bankcoins could not offer.

“Most recently, for reasons not pertinent to this issue of Dirt Roads, the public started demanding additional features that weren’t native to bankcoins, namely:

Lower all-in transaction costs to perform certain intermediation activities

Higher yield for their cash savings at (to be proven) comparable risk levels

Higher (perceived) control over currency vs. what happens in a system pivoting around central banks and governments”

- #4 | A Taxonomy of Currency: from Coin to Stablecoin (Dirt Roads)

These new needs were addressed with the advent of public blockchains and smart contracts, which paved the way for a new kind of money: stablecoin. Stablecoins retained the core properties of bankcoins and coin while adding composability with blockchain networks and decentralized finance (DeFi) applications.

Figure 4: An illustration of the stablecoin monetary stack

Source: #4 | A Taxonomy of Currency: from Coin to Stablecoin (Dirt Roads)

As I covered in my previous post, there are several models for creating stablecoins. The fiat-backed is the simplest and most widely used model. Under this model, an issuing company receives fiat deposits from users, stores them in reserve bank accounts, and mints an equivalent amount of stablecoins on the blockchain. Users can redeem their stablecoins for the underlying fiat through a redemption process facilitated by the issuer.

The full backing nature of fiat-backed stablecoins ensured price stability and made them highly popular within the DeFi ecosystem. Tether’s USDT (with $119 billion in circulation) and Circle’s USDC (with $35 billion in circulation) are the leading examples, together comprising over 80% of the total stablecoin market share.

Despite their innovative nature, however, USDT and USDC are still tied to the traditional banking system. They function as aggregators of bankcoins and behave more like payment rails layered on top of the existing monetary stack with enhanced features and yield.

And despite their convenience and accessibility, these fiat-backed stablecoins introduce several new problems:

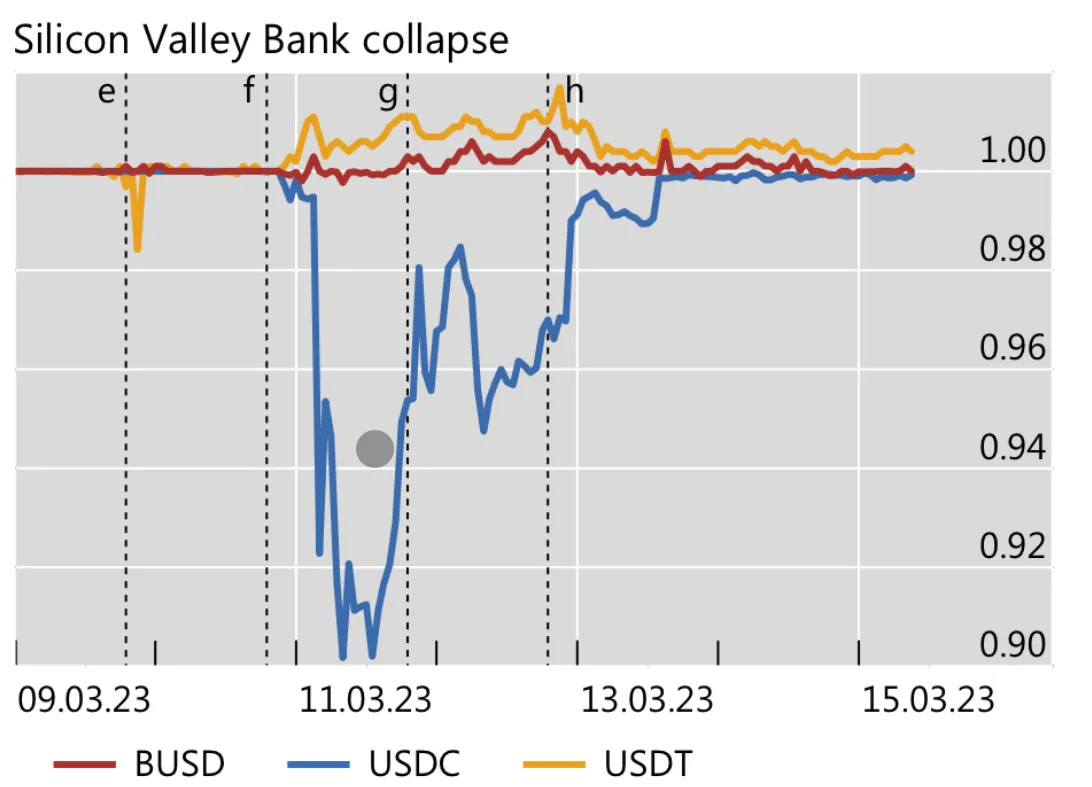

Figure 5: Volatility in stablecoin prices during SVB collapse

Source: Stablecoins Versus Tokenized Deposits: Implications for the Singleness of Money (BIS)

Counterparty Risk: Bankcoin reserves are typically invested in safe and liquid assets like cash and short-dated U.S. government securities. Although credit risk is minimal, counterparty risk is elevated as only a small portion of the bank deposits are protected by FDIC insurance. For instance, Circle had a significant portion of its cash reserves held at SVB. Had SVB not been bailed out by the FDIC, USDC could have permanently lost its 1:1 peg to USD.

Yield Sharing: Issuing companies capture 100% of the yield generated from short-term U.S. government debt while depositors, who take on the counterparty risk, receive no compensation. Imagine users making a bank deposit and receiving no interest in return.

Fragmentation: Although they represent digital versions of bankcoins, fiat-backed stablecoins are not interoperable. For example, a user holding USDT cannot directly pay a merchant who only accepts USDC without first swapping USDT for USDC on an exchange. This friction mirrors the pre-central bank era when one bank’s notes were not always accepted at full value by another.

Strengthening the Weakest Link: Banks

A chain is only as strong as its weakest link, and in our current monetary system, banks are that weak link. To address this vulnerability, we need to explore alternative methods for distributing new money into the economy.

One potential solution is to expand the role of central banks through the issuance of CBDCs as they have the potential to provide customers with a superior form of money.

“In oversimplifying terms, retail CBDCs would allow customers (private and business) to deposit money directly in central banking accounts. This would dramatically reduce credit and counterparty risk; differently from banknotes, our commercial banks deposits bear some level of risk above what guaranteed by deposit insurance schemes (if the bank goes under it’s not straightforward you can get all your money back).”

- #3 | The Dangerous Ambition Behind CBDCs (Dirt Roads)

The introduction of CBDCs would pose a fundamental threat to the existing banking system. After all, why would a customer choose an inferior version of money when they can access the safest form directly from its source?

However, implementing CBDCs presents significant operational complexities and raises serious concerns about privacy and government control, which run counter to the foundational principles of decentralized systems like blockchains.

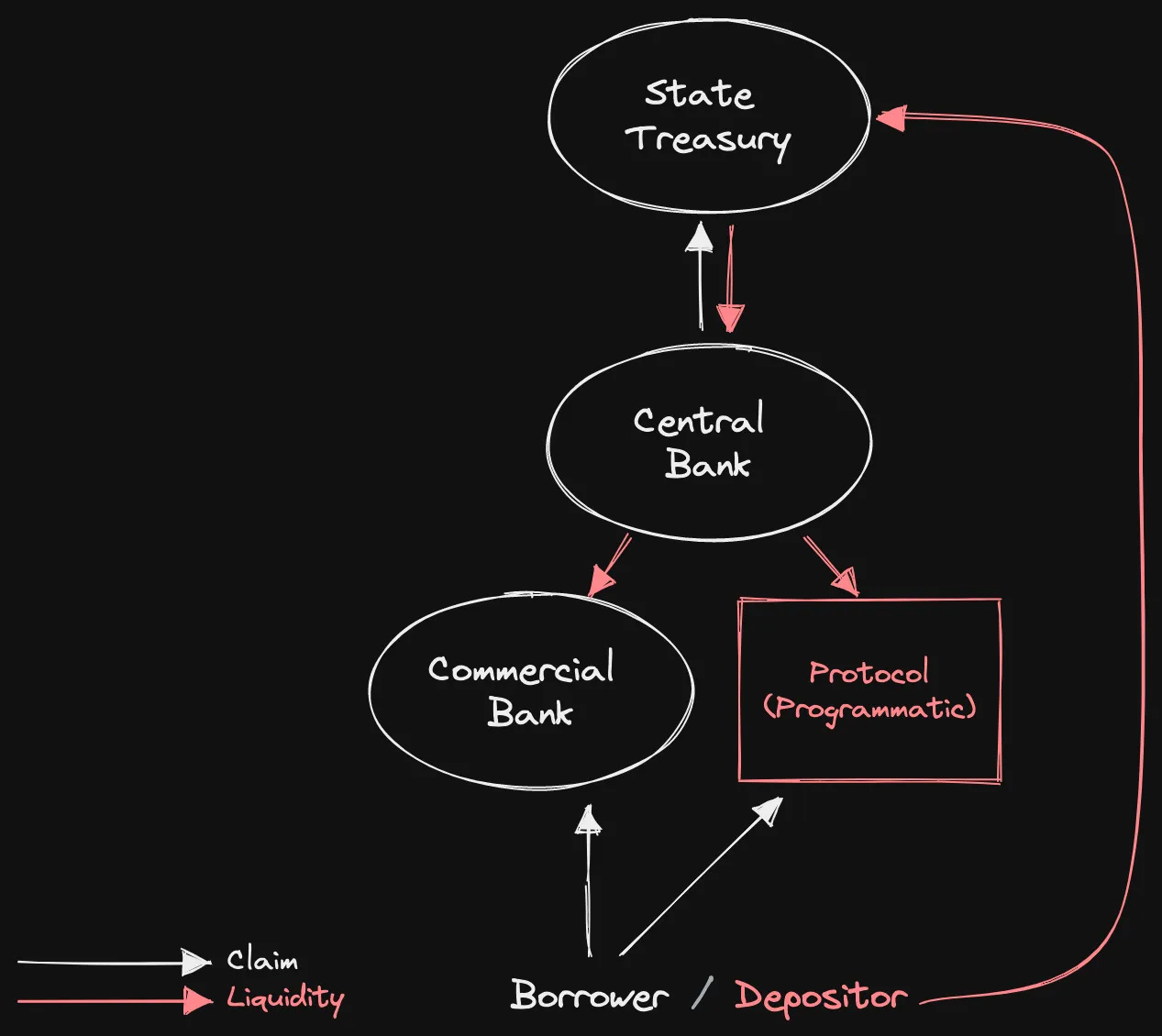

Figure 6: Illustration of the new monetary triangle

Source: #53 | Banking is Broken, Hallelujah (Dirt Roads)

An alternative approach would be to distribute money through a new network of qualified intermediaries. Instead of relying on bank to identify lending opportunities and accurately price credit (a task at which they have historically struggled), these intermediaries could serve as simple conduits that aggregate and pass through credit assets.

Under this model, banks would no longer monopolize the lending process and the intermediaries could pledge eligible assets as collateral to access newly issued money, providing a safer and more transparent means of money distribution. Such intermediaries could range from centralized entities that pool standardized and low-risk assets to algorithmic systems that use smart contract to manage credit issuance and repayment.

Circle’s USDC, for example, already operates as a fully reserved money market fund. It aggregates customer deposits and invests them in safe, liquid assets, offering seamless integration with the DeFi ecosystem. While this approach offers simplicity and stability, it also reintroduces some of the same risks and limitations we’ve previously discussed.

On the other side of the spectrum are algorithmic conduits. Under this model, a sovereign issuer (or decentralized protocol) could whitelist a set of qualified collateral assets that are eligible for financing through smart contracts. Users would then be able to pledge these assets independently and manage the associated liabilities without requiring a centralized intermediary.

MakerDAO is an example of this approach. Users can deposit approved crypto collateral to mint DAI, its decentralized crypto-backed stablecoin. This model introduces a high degree of autonomy and decentralization, but the high volatility of crypto assets forces MakerDAO to implement strict over-collateralization requirements that reduce the users’ capital efficiency, putting MakerDAO at a structural disadvantage.

But what if we combined the best of both worlds? Imagine using an algorithmic framework similar to MakerDAO’s but with more stable Real World Asset (RWA) collaterals like U.S. Treasuries?

This is precisely what M^0 aims to achieve.

M^0: A New Way to Issue Cryptodollars Onchain

M^0 is an open protocol built on the Ethereum network that enables approved participants, known as Minters, to issue a new type of stablecoin called “M”, which is backed by U.S. Treasury bills.

M^0 envisions a future where crypto is more than just an instrument for speculative trading and could become the backbone of a new global financial system. To realize this vision, however, the industry needs a new form of digital money that is not merely a tokenized representation of existing bank deposits, which are inherently tied to the traditional banking system and carry the same systemic risks.

This is where M comes in. By redesigning the monetary stack from ground up, M^0 has created a “cryptodollar” backed entirely by U.S. Treasury bills, widely considered the safest asset in the financial world. M^0 acts as the sovereign issuer of the system, while Minters operate as qualified intermediaries using smart contracts to issue their own versions of digital “bank notes”.

With this design, M combines the convenience of digital money with the core characteristics of physical cash, attributes that have been largely lost in the shift to digitization. Just like cash, M cannot be frozen or seized without due process, ensuring it remains credibly neutral. This neutrality means that the core protocol cannot arbitrarily block or discriminate against any user.

Furthermore, unlike fiat-backed stablecoins that rely on customer deposits held in traditional bank accounts, M is designed to operate independently of banks. This structure eliminates additional counterparty risks associated with holding deposits above FDIC insurance limits.

M’s ultimate vision is to serve as the foundational layer of digital money. While M can function as a standalone stablecoin, the goal is for it to serve as raw material for developers and financial institutions to create innovative tools, such as new forms of collateralized stablecoins. The name M^0 (rather than M^1) reflects this aspiration: a desire to be the fundamental starting point for a fully onchain financial ecosystem.

M^0’s new model also aims to address structural inefficiencies that are hampering existing stablecoin products:

(1) Solving Interoperability and Fragmentation

One of the key challenges with existing stablecoins is fragmentation. Each issuer creates its own token, leading to a proliferation of assets that are not easily compatible with one another. M^0 solves this by establishing a unified platform where all Minters issue the same stablecoin using a common collateral base, and add liquidity within the same network.

This standardization ensures that M and any of its derivatives are fully interoperable, similar to how dollars deposits at different banks are interchangeable. It creates a seamless ecosystem that eliminates the friction and fragmentation observed in today’s stablecoin market.

(2) Aligning Yield Distribution with Value Creation

In the current landscape, centralized stablecoin issuers like Tether and Circle capture all the yield generated from user deposits, leaving value creators such as DeFi protocols, dApps, and users disconnected from the economic benefits. Although some issuers have recently started sharing a portion of this yield due to rising competition, these decisions are made at the discretion of the centralized entities and can be altered at any time.

M^0 takes a different approach by programmatically distributing the yield from the underlying U.S. Treasuries across all permissioned issuers, who can then share it with liquidity providers and end-users. This decentralized model ensures that those who contribute to the system’s value are compensated and aligns incentives across the entire ecosystem.

(3) Enhanced Capital Efficiency

M^0 also offers greater capital efficiency compared to other decentralized stablecoins. MakerDAO, for example, primarily uses volatile crypto assets as collateral, which requires significant overcollateralization and reduces capital efficiency.

While MakerDAO has attempted to incorporate offchain assets like real-world bonds, its architecture was not originally designed for such collateral types and had challenges scaling effectively. In contrast, M^0 is purpose-built to utilize high-qualify offchain assets such as U.S. Treasuries and provides a more secure and efficient framework for minting stablecoins.

Keys to Continued Success

The M^0 protocol launched in July 2024 and Minters have already minted $42 million worth of M on the network. The fundamental structure and vision for M^0’s success are in place, and the following elements will be critical in driving its continued growth.

(1) Reliable Off and Onchain Oracle

Since U.S. Treasury bills will be held by Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) in the offchain world while their derivative, M, operates on the blockchain, maintaining a reliable and accurate oracle to connect the two will be very important. If liquidations of T-Bills or M occur, the stability of the protocol relies on synchronized data flows.

This mirrors the dynamics of exchange-traded funds (ETFs) where the digital representation must stay aligned with the actual physical asset held by custodians. However, unlike ETFs that operate under the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) legal framework, smart contracts lack similar legal enforceability within the traditional financial system.

Tether and Circle don’t face this challenge since they manage both on and offchain records as centralized issues. MakerDAO also avoids this issue by keeping both its collateral and stablecoin entirely onchain.

Figure 7: An example collateral update flow on M^0

Source: M^0 Adopted Guidance (July 2024)

For M^0, Validators act as ecosystem auditors and are tasked with verifying the financial representation of the collateral and the cryptodollar are accurate while ensuring the underlying legal structures comply with the protocol’s guidelines. Their specific roles and responsibilities are outlined in M^0’s Adopted Guidance released in July 2024.

(2) Scalable Onboarding Process

To address the oracle challenge and ensure protocol stability, M^0 has set high onboarding standards for new participants, including stringent requirements on legal entity structuring and contractual agreements between key stakeholders. These standards, also set forth in the Adopted Guidance, must be met onchain, from a technical perspective, as well as offchain, through legal frameworks.

If the onboarding process becomes too complex, however, it could discourage new entrants and impede growth. To balance high-level of standards with broader adoption, M^0 offers standardized legal templates and operating agreements that adhere to the protocol’s guidelines, simplifying the process for new participants without comprising the integrity of its model.

(3) Attracting Liquidity

The success of any financial network depends on its ability to attract liquidity. For M^0 this means creating strong incentives for stablecoin participants to migrate from existing products to the new infrastructure.

The value proposition for Minters is compelling. M^0 provides a streamlined framework for issuing offchain asset-backed stablecoins while allowing them to earn the yield spread between T-Bill returns and protocol fees. From a market maker’s or end-user’s perspective, M^0 offers access to programmatic yields and an interoperable stablecoin that doesn’t fragment liquidity.

Despite these incentives, however, challenging the established dominance of USDT and USDC will be a formidable task. Similar to how VISA and Mastercard dominate payment networks, Tether and Circle already enjoy strong brand power and entrenched network effects within the stablecoin network.

However narrow the road to victory may be, M^0 has the potential to reshape the stablecoin landscape and build a more resilient foundation for DeFi. It has the vision, a robust financial foundation (having raised nearly $60 million in seed and Series A funding), and an all star team to drive execution. With these resources, M^0 must unite smaller stablecoin issuers and attract liquidity providers and DeFi protocols to adopt M.

(4) Decentralized Governance and Strong Community

One of MakerDAO’s greatest strengths is the quality and engagement of its community members. It has set the standard for decentralized stablecoin issuance, fostering a culture of innovation that has led to many successful creations in the DeFi space, including M^0 itself.

M^0 aims to replicate this success through a unique two-token governance system that promotes active participation. However, the founders also believe that effective governance does not mean putting every operational decision to a public vote. Their philosophy is that only critical protocol changes should require broad community input, while more specialized decisions should be managed by domain experts.

In line with this approach, M^0 has avoided indiscriminate airdrops of its governance tokens and instead focused on cultivating a curated and intentional community of governance participants. Over time, this strategy will foster more thoughtful protocol development and help avoid the pitfalls that have plagued many other decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs).

Looking Ahead

With the successful launch of M, what lies ahead for M^0?

Out of the many interview the co-founders have conducted, one particular conversation with Rebank stood out to me and articulated what M^0 ultimately aspires to be.

Paraphrasing Luca’s points from the interview:

The internet has transformed the world by making it easier for people to exchange both data and value. Through Ethereum, the first general-purpose smart contract-enabled blockchain, we were able to achieve a decentralized way of exchanging data through its distributed computing layer. However, exchanging value on Ethereum is less efficient, as existing financial intermediaries are still finding best ways to interact with other using this infrastructure.

M^0 aims to address this gap by creating an overlay on Ethereum that specializes in middleware, a financial intermediation layer purposefully designed to enable financial institutions like collateral providers, asset managers, and liquidity providers to interact seamlessly and efficiently.

Luca envisions a future where financial institutions can move their assets onchain and build any type of financial product in an open-source and modular way. He likens the financial stack to a technology stack, where it can be divided into frontends and backends.

Frontends are the interfaces that engage directly with customers, while backends represent the infrastructure that powers them. For example, a traditional bank combines both customer facing services (frontend) and core banking infrastructure (backend).

M^0’s goal is to recreate the financial system on the blockchain by abstracting away the backend from the frontend. By focusing on building a standardized backend infrastructure, M^0 will allow financial institutions to concentrate on delivering innovation without needing to rebuild the underlying systems from scratch.

The introduction of M, its cryptodollar, is just the first step. Once M is well established, it will open up endless possibilities for what else can be created on this new system. From onchain versions of TradFi services to entirely new types of DeFi services, M^0 could become the backbone of a more open, interconnected financial world.

“The ambition for M^0 is to be an open source, open architecture backend for any regulated front-end that is a financial intermediary across the globe. It seems very abstract, but it’s not. Stablecoin is the first really pragmatic example we have in mind, but there are so many things that you can envision... [omitted] There is a lot to do, and I’m super excited for what is yet to come.”

- Luca Propseri (Building Decentralized Infrastructure for the Global Financial Industry)

The success of this vision is still work in progress and the challenges are significant. But it’s a bold and exciting future they are working to build. For that, I am rooting for their success.

References

Bank of England (2014). Money Creation in the Modern Economy.

Arthur J. Rolnick, Bruce D. Smith, Warren E. Weber (1996). The United States’ Experience with State Bank Notes: Lessons for Regulating E-Cash (A Progress Report).

Rodney Garratt and Hyun Song Shin (2023). Stablecoins Versus Tokenized Deposits: Implications for the Singleness of Money.

Chris Brown (Unknown). Quora Response to “How do banks make money?”.

Rebank (2023). Building Decentralized Infrastructure for the Global Financial industry.

Luca Prosperi (Various). Dirt Roads.

M^0 Research (Various).

M^0 Foundation (2024). Adopted Guidance.

rwa.xyz.